Written originally for Topics Magazine in Taiwan, this version of “Four Stages” contains additional unpublished material specifically for Going Awesome Places. Original version is also on Joshua Samuel Brown’s blog.

Childhood: Consequence-Free Dining at the Night Market

Will was on assignment in Taiwan, one of a group of bloggers, YouTubers and other influencers sent by the Tourism Bureau to produce Millennial-friendly content promoting Taiwan on the internet. It was his first day in town, so I figured the night market was a good place to start.

I texted my suggestion. When he replied, “Take me to where the locals go,” I knew I was dealing with a fellow travel professional.

Read more on Taiwan

- 12 day Taiwan itinerary

- Where to stay in Taipei – a neighbourhood guide

- Why you need to visit Taiwan

How to get the best deals in travel

- Hottest deals – Bookmark the travel deals page.

- Car rentals – stop getting ripped off and learn about car rental coupon codes.

- Hotels – Use corporate codes or get Genius 2 tier with Booking.

- Flights – Have you ever heard of the “Everywhere” feature?

- Insurance – Make sure you’re covered and learn more about where to buy the best travel insurance.

In This Article

While Taipei’s night market scene is well-known, your casual traveler generally tends to stick to the big three as promoted heavily by the folks in the aforementioned bureau. Specifically known are the ever-popular yet nefariously confusing Shilin (whose confusion begins with the fact that if you get off the MRT at the station bearing the same name you’ve gone a stop too far), the more traditional Raohe market and the tourist friendly Ningxia market.

But Will had requested a local experience, so I brought him to Jingmei, where the only occasional occidental face seen chomping down a comically Flintstones-sized grilled octopus tentacle slathered in teriyaki sauce not my own generally belongs to one of the long-term Western denizens of the neighborhood (still reasonably affordable by dint of its being nearly on the city’s outskirts).

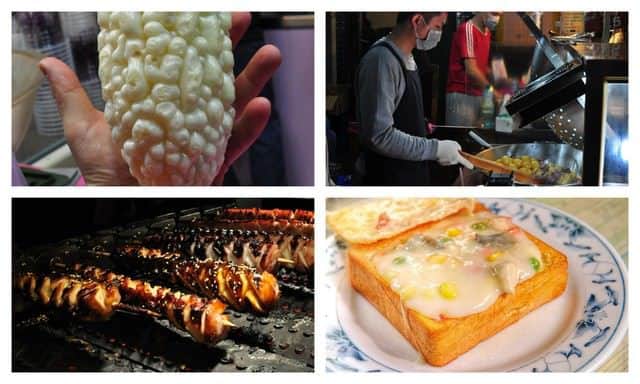

Our epicurean excursion began with the tentacle, grilled to moist perfection over hot coals, and I felt strongly that the folks at the bureau would appreciate the film Will was making of our eating this most monstrous of appetizers. After we’d wolfed down our Lovecraftian snacks, Will asked me to introduce him to another typical night market dish. Across the lane, an old woman stood behind a metal grill preparing one of Taiwan’s more well-known dishes, oh ah jen, the oyster omelet. This artery-clogging dish consists of a dozen or so shucked oysters cooked on a generously lard-lubricated grill in a batter made from egg and corn starch, fried to the consistency of cold motor oil and served slathered in red sauce.

As a travel blogger, Will couldn’t resist ordering the dish, and being a glutton for punishment, neither could I.

“Take that, coronary health, hashtag heart-smart” I said, doing my bit to promote Taiwanese cuisine to Will’s YouTube subscribers by shoveling a plastic forkful of weapons-grade cholesterol in my mouth.

Will had heard about another typical Taiwanese dish, the famous night market beefsteak. Following the omelet I brought him to a stall specializing in the dish, explaining as we walked the difference between this dish and its more well-known variant.

“Whereas your North American steak is served a cappella, a night market steak is part of an ensemble act including spaghetti, sauce, and a raw egg cracked on top of the beef. The whole thing is served on a heated steel plate.”

“But is it good?,” Will asked. I quoted Hamlet in reply.

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

Save money on your trip to Taiwan

At the time, Joshua was working for MyTaiwanTour, a company based out of Taipei where they offer package and custom-tailored solutions for English-based tours around Taiwan.

Save 5% on tours with MyTaiwanTour by using code WILL19.

Will decided to give #IronPlateHeartAttack a pass, so we headed for lighter fare, a dozen deep fried sweet potato balls. Though already stuffed, we felt something sweet was in order.

“How about some cake?” I suggested.

Close to the market’s entrance, a young baker was busy taking a cinderblock-sized pound cake out of a massive oven. Of the various dishes we’d seen and consumed in the past hour, this one struck us both as the least nightmarket-y of the lot.

“What’s in it?” Will asked the baker.

“Flour, eggs, water, sugar. Very simple.”

Will was intrigued. But he had another question. This being his second trip to Taiwan, he’d noted with curiosity that despite the national love for highly caloric dishes, most Taiwanese were fairly svelte.

“How do you stay so slim, what with your working in a night market?”

The baker answered by lifting the tray filled with steaming pound cake over his head and shaking it several times like a Russian weightlifter before upending the thing with a dull thud on the stall’s metal counter.

“I exercise at work,” the baker answered.

The cake was delicious, and if it wasn’t the lightest thing we’d had all night it was likely the healthiest. Though fully sated, we headed back into the market for one last round. After all, the night was still young.

Maturity: Dining for cultural empowerment

“Ach sis, mate, you need to let me take you to a proper tribal restaurant,” Tobie said, and though I’d planned to settle for some al fresco dining along Wulai’s Old Street after our hot spring soak, my South African friend had arranged the trip. “These places are for tourists, man. What kind of travel writer are you?”

An off duty one, I was about to answer, but I held my tongue. Tobie has become increasingly passionate these past years about the promotion of Taiwan’s indigenous cultures, so I should have expected that this particular hot spring trip would include an educational component of some sort. A short drive up from the Old Street brought us to a part of Wulai more off the tourist trail, and moments after parking Tobie was being greeted warmly by the proprietress of Taiya gourmet restaurant(泰雅美食餐廳), an older, more deeply traditional restaurant perched precariously on the side of a hill overlooking the river valley.

“They seem to know you here,” I commented.

“Oh sure,” Tobie replied nonchalantly. “I come by here often. But yeah, I was probably the only Western face seen here documenting the immediate aftermath of Typhoon Soudelour – and the amazing recovery efforts afterwards. If the eldest son were here, we’d soon be drinking xiao mi jou (millet wine) and singing traditional Tayal songs together.”

But the son wasn’t present, so I was spared a rousing duet of Rimui So La Rumui Yo and instead got to hear Tobie ordering dishes off the menu. In short order, the dishes began arriving, and as they did Tobie began describing each in loving detail.

“Ach, this is good stuff. Stone-roasted mountain pork cooked with magao.”

Magao, Tobie told me, was a locally-grown peppercorn, with a surprising citrus zest. It goes fantastically well with either pork, chicken or (especially) fish, and in recent years some top-level chefs have discovered it and started incorporating it in fusion dishes. You can buy a jar of it on the street in Wulai to experiment with.

“This, this is real food, mate. It’s important to experience places like this, man. Do our part to keep local culture alive.”

The next dish to arrive was stir-fried fiddle-head fern, a vegetable harvested wild in the mountains, followed by binlang hua, the fronds from the betel nut palm.

“The best part of the plant, in my opinion,” Tobie said, which I found ironic coming from a man who’d once made a name for himself documenting Taiwan’s notorious betelnut girls.

The last dish to arrive was San Bei Ji, Three-cup Chicken, but in place of the usual rough-cut chunks of chicken, the bowls contained pieces that clearly came from a much smaller bird, like a quail, I thought. “See how small the chicken is? Mountain partridge – raised locally.” A quintessentially Taiwanese dish, 3-Cups Chicken is so named because its basic ingredients, in addition to chicken, are a cup each of soy sauce, rice wine and sesame oil. But as Tobie pointed out, the folks at the (name) restaurant had found a way to make it with tribal flair.

The food was excellent, and the meal filling on both a physical and cultural level. Leaving the restaurant, I headed across the road to grab a cup of coffee from 7-11, and for the second time that day Tobie stopped me.

“Come on man, don’t get a bladdy 7-11 coffee. Let me bring you over to Mei Lu’s coffee shop in the Atayal Cultural Museum.”

Once again my friend proved correct, though I could have done without the addition of magao. I felt the spice which had so well complimented the pork merely confused the coffee, which several shots of Mei Lu’s complimentary rice wine consumed alongside the coffee failed to clarify.

Middle Age: The Bill Comes Due

Doctor Yu shook his head as he looked over the results of my recent blood draw on the screen in front of him.

“Your cholesterol is elevated from your last checkup. Have you cut back on fried foods as I suggested?”

“Somewhat,” I answered vaguely.

“Cut back more. No more than once a week.”

“Do you mean one fried item a week or one day weekly in which I should solely eat fried food?”

Dr. Yu was not going to dignify the question with a response. He was a busy man, with two dozen patients yet to see before lunch.

“You should be staying away from fried food anyway,” he continued. “As I told you on your last visit, it can trigger your gout.”

Ah, gout. Lifelong unwelcome guest, enemy and Teacher, shared with luminaries from Henry the Eighth to Benjamin Franklin. The Teacher had made his first appearance right here in Taiwan two decades ago after an all-I-shouldn’t-eat crab buffet, and after many years’ absence had recently returned for more regular calls. In an effort to keep the big G from my doors, I’d cut all shellfish from my diet. And though night market foie gras isn’t yet a thing in Taipei, I had a ready-made excuse outside of basic decency to turn it down should this ever change.

“I’ve been pretty good about staying away from purine-heavy foods,” I said hopefully. “More pasta and bread, less meat.”

“Yes, about that,” Dr. Yu said, swiveling his monitor until it stared me in the face. “The third number down is your blood sugar. You are now in the pre-diabetic stage, so you should probably not be making carbohydrates the staple of your diet. It just becomes sugar in the body.”

“What about rice?”

“Cut down on rice, too.”

My list of wisely edible foods was shrinking fast.

“So what can I eat?” I asked.

Dr. Yu paused, and removed his spectacles in a way that made him seem especially sincere.

“Your best strategy is to not eat too much of any one thing. As you say in the West, ‘Eat the Rainbow’. Many different things at each meal. Such as you will find at the buffet downstairs.”

I refrained from saying that the last time I’d heard that expression, people still thought that margarine was “healthy”. Doctor Yu replaced his glasses and gestured towards the door. My appointment had already exceeded its allotted time. I got up to leave.

“How about bitter melon?” I asked at the door.

“Eat as much bitter melon as you like,” replied the doctor.

I was about to discover exactly how much bitter melon that was at Taipei’s most convenient (particularly for those who’ve just received advice of the ‘you’d better change your ways’ variety) vegetarian buffet in the hospital’s basement. A steam table of dishes crafted to follow both Hippocratic oath and Buddhist doctrine lay before me.

In its natural form, the bitter melon gourd resembles something like a Klingon marital aid, phallic and covered with bumpy nubs. Buffet chefs had sliced it into circular sections about the thickness of a 50 NT coin and thrice the diameter, the outer rings an almost fluorescent green, dimming down to a pale white towards the interior, adding little, perhaps in keeping with the first noble truth of Buddhism about life being suffering. Taking my well-being seriously, I filled the corner cube of my cardboard tray with eight slices, arranging them neatly as the smiling nun behind me looks on in passive admiration. I take other items down the line, including a braised gluten and tuber mix, a healthy (literally and figuratively) helping of mixed vegetables, several cubes of bean curd, asparagus and carrot sticks wrapped in long-since-limp seaweed to resemble sushi’s cousin that’s found religion, and two cubes of jiggling yellow custard sprinkled with coconut.

I’d devised a strategy to consume the bitter melon. But I needed first to know what I was up against. The first slice, eaten alone, was unbearably bitter. The second I ate wrapped around sushi’s spiritual cousin in the other, the bitter melon almost completely overwhelming the asparagus-carrot-seaweed roll. A mouthful of braised gluten in brown sauce restored equilibrium, but six slices still stared up at me.

I wrapped the third around the custard, hoping that bitter and sweet cancel each other out in both pancreas and tongue. Only my next blood test will speak for the former, but as for the latter the experiment worked well enough to allow for a repeat with the fourth slice shortly after swallowing the third.

Having now used the dessert portion of the meal as camouflage, I was forced to combine two more slices with the savory bean curd. By this point the bitter melon had coated my tongue to the point that everything tasted like Chinese medicine. I couldn’t stomach the final two slices, so I opted for the spiritual path instead, sliding them into the compost bin so that they might lower the blood sugar of some lucky pig.

Death: Embracing Mortality with Coffin Toast Bread

I hit Tainan feeling like death warmed over, thanks to a cold that had chosen to make its presence known just past the Banciao HSR station. Too late to turn back from my commitment, the only sensible thing to do was to go looking for a coffin. Luckily, I was in the Taiwanese city known for a culinary oddity known as Guan Cai Ban, or “Coffin Toast Bread.”

“Where’s the best Guan Cai Ban in town,” I asked my taxi driver. I might as well have handed him a business card reading Tourist, but I didn’t care.

“Chi Kan,” He answered “Famous place. You had Guan Cia Ban before?”

I told the driver that I’d had the dish before in Tainan, years ago, and didn’t remember much outside of having liked it. The truth was that I’d visited one or two spots in Taipei claiming to serve it, but that I’d found these to be pale imitations. Some foods – San Francisco Sourdough, Philly Cheese Steak, Brooklyn Egg Creams – are justifiably best sought out in the city for which they’re named, and such is the case with Tainan Coffin Bread.

The driver dropped me off in front of a bustling, if somewhat rundown-looking, mall on Hai’an Road in the West Market District, and a short walk through a maze of alleys brought me to a colorful, simple eatery with low tables and metal chairs, inside of which a dozen or so diners were scooping creamy filling out of bread with spoons. Although the placards inside and out indicated that Chi Kan was now primarily popular with tourists, the place still retained a local greasy spoon vibe, and after a bit of chit-chat with my waitress concerning what varieties of Guan Cai Ban were available (two, it turned out), I settled on the traditional non-curry version. A few minutes later I was served a slab of bread about 3 times the thickness of your standard bread slice. It had been deep fried, and was still oily to the touch, and filled with a creamy, milky chowder of seafood and vegetables.

Though I’d eaten the dish before when I’d first visited Tainan in the nineties, my palate was now far more experienced and this time I found the dish especially curious, far removed from the usual Taiwanese spicy palate. It tasted more like the Chicken à la King of my long-lost childhood than anything I’d eaten in years. It was delicious, and filled me with something akin to nostalgia.

I waved the waitress over to order a second serving.

“This really tastes like a Western dish,” I remarked when it came.

“It kind of is,” she replied. “There were a lot of American soldiers stationed around here after the Japanese left, and when the Americans came, the chef realized he’d have to start catering to different tastes. So he invented this dish.”

“So it’s not really a ‘traditional’ Tainan dish?”

The waitress shrugged.

“It is now. But it’s not ancient, if that’s what you mean.”

“But what about the name coffin toast bread”?

“That came later. Because it looks like a coffin.”

I could see the resemblance to a Chinese style coffin. I dug in to my second serving, which was even greasier and even more delicious than the first. I wasn’t worried about my health. That ship had already sailed.

Joshua Samuel Brown is the co-author of thirteen titles for guidebook titan Lonely Planet and a regular contributor to their World’s Best Food series. His most recent book Formosa Moon is a dual-voiced cultural exploration around Taiwan. Formosa Moon is what Henry Miller and Elizabeth Gilbert might have produced during a lengthy literary exploration of Taiwan. Get your copy at www.josambro.com. Follow Joshua on Twitter @Josambro.

Joshua Samuel Brown is the co-author of thirteen titles for guidebook titan Lonely Planet and a regular contributor to their World’s Best Food series. His most recent book Formosa Moon is a dual-voiced cultural exploration around Taiwan. Formosa Moon is what Henry Miller and Elizabeth Gilbert might have produced during a lengthy literary exploration of Taiwan. Get your copy at www.josambro.com. Follow Joshua on Twitter @Josambro.